In ecology, the reproduction of structural biases has been evidenced, but their relationship to the structure of knowledge has not been fully analysed. One example is the discussion of the existence of a temperate bias that shapes our understanding of the tropics. Here we conduct a comparative scientometric analysis of tropical and temperate ecology in different time periods (based on approximately half a million peer-reviewed articles) to understand how ecological knowledge has been shaped by socio-economic and geopolitical influences. We demonstrate a dramatic effect of globalisation on the scientific production of ecology, expressed in a higher frequency of multinational articles and a more connected network of international collaborations. The structure of citations and authorship points to an under-representation of the Global South, although the BRICS countries are prominent in the 21st century. The conceptual structure indicates a common pool of concepts, but marked differences in the epistemic focus between tropical ecology (focus on applied ecology) and temperate ecology (focus on ecosystem ecology). We also observed a high frequency of geographic locations as key concepts in the tropics, which we interpret in light of the geopolitics of knowledge. In conclusion, although we observe that knowledge from the Global South is an integral part of ecology in different periods, we confirm that North-South inequality is transferred to the temperate-tropical relationship, confirming the existence of a temperate bias.

We must never conceal from ourselves that our concepts are the creation of the human mind that we impose on the facts of nature. Arthur Tansley, 1920

Ecological differences between tropical and temperate regions have long been a subject of scientific study in ecology and evolution (e.g., Ricklefs and O’Rourke, 1975; Vernberg, 1981; Sun et al., 1997; Staggemeier et al., 2020). However, the way in which research has been developed and perceived is markedly different between the two regions. As Raby (2017) put it, "why are there scientific journals, professional associations and research institutions dedicated to tropical biology while 'temperate biology' remains an unmarked category?"

The existence of a ‘temperate bias’ (Zuk, 2016; Stutchbury and Morton, 2023) has been proposed as a possible explanation. This hypothesis postulates that temperate regions have historically been the model system to which the tropics are compared, which would entail a series of problems. The existence of a temperate bias could hinder both the appreciation of the extent of variation in nature (Zuk, 2016; Stutchbury and Morton, 2023) and the development of accurate models, which questions the validity and generality of ecological and evolutionary research. One indication of this bias could be the fact that ecology articles that present themselves as global tend to under-represent research from southern countries and tropical regions (Stroud and Feeley, 2017; Nuñez et al., 2019, 2021), also, research study that showed a strong geographical imbalance in publication patterns and between different taxonomic groups for specific topics between the tropical and temperate region (Culumber et al., 2019). However, to date, we have no concrete evidence of this bias or more solid explanations for the Tropical-Temperate issue in ecology.

The coloniality of knowledge/power (Hirschfeld et al., 2023) and the geopolitics of knowledge offer tools for analyzing how historical, political, and institutional inequalities condition the production and circulation of knowledge, elements that are relevant for situating the tropical–temperate issue. The geopolitics of knowledge, in particular, examines the structures that shape knowledge production from a historical perspective (Medina, 2014) and highlights the relationship between scientific practices and the spaces where they are produced, with an emphasis on political conditions and international collaboration networks (Barros, 2019). In ecology, geopolitics has been highlighted as fundamental to understanding how ecological knowledge is constructed in specific places that are not neutral spaces. De Bont and Lachmund (2017), for example, show that the selection of habitats as objects of study and the ways in which they are classified and mapped directly influence categories and hypotheses. Bocking (2015) argues that ecological concepts emerge from practices situated in concrete locations (such as field stations, nature reserves, or museums) that are not mere scenarios but materially and culturally shape ways of seeing, ordering, and interpreting nature. This body of work is fundamental to understanding how specific histories and geographies structure problems, methods, and interpretations, providing insights for critically contextualizing the debate on the tropical–temperate distinction.

Here, we conducted a comparative analysis between global, tropical and temperate ecology by approaching them not only as geographical or biological entities, but also as historical and socio-political constructs. We do this through a scientometric analysis of ecology articles published in two time periods, 1960–1999 and 2000–2020, roughly capturing drastic changes which occurred by globalisation, up to the pandemic caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus. In particular, we analyse historical changes in the frequency of multi-country articles, spatial patterns of international collaborations and conceptual networks for the different data-sets. Our interest goes beyond purely describing patterns; we want to assess the relationship between the social/geographical distribution of research and the structure of ideas over time, focusing both on geopolitical relations and on the patterns of knowledge circulation that enable us to explain them.

MethodsWe carried out a bibliometric analysis, according to the standard for bibliometric research adapted from Cobo et al. (2011) and based on the protocols available in the updated Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement, which provides comprehensive guidelines for correctly reporting systematic literature reviews (Page et al., 2021).

Data design and collectionIn order to identify the search formula that best fits the objectives of the study, we carried out a preliminary evaluation of the literature on tropical and temperate ecological research. There are different methodological approaches to comparing tropical and temperate regions. The prevailing approach is to explicitly compare some specific aspect of ecology between the tropical and temperate regions. More recently, a study comparing the tropical and temperate regions has also been carried out based on the selection of specific topics and taxa (Culumber et al., 2019). In our case, we have chosen to compare the corpus of research we found when searching for the topics “temperate” and “tropical” independently, within the global corpus of research on ecology, given that the objective is not to compare the use of any specific topic, but rather the conceptual and social structure of knowledge.

We chose to use the Web of Science (WoS) database from the Institute for Scientific Information (ISI) to obtain the data. ISI is among the largest and most widely used global databases of publications in various languages. We defined six searches (as described in Supplementary material Table S1) for articles (peer reviewed) published between 1960 and 2020, divided into two time periods (1960–1999 and 2000–2020) for three regions (Global, Temperate and Tropical), totaling six datasets. The systematic search for the period before 1960 proved to be limited due to the high incidence of missing information in electronic format. The division into two periods aims to observe the evolution of patterns of representation by parents and collaborative networks, as well as the use and frequency of concepts, considering the consolidation framework of the so-called globalisation of science, which gained greater momentum from the end of the 20th century (Gui et al., 2019), thus separating the 20th century from the 21st. In this way, we seek to understand the structure of the field before and after the effects caused by the internationalisation and consolidation of an “information society” (Castells, 2006). Furthermore, the search was conducted up to the year in which the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic began, given its impact on various aspects of life and work, especially science and scientific production.

We exported the complete list of articles by country for each dataset from WoS. As the “Global” dataset includes all the records found for the “Ecology” area of WoS, for the subsequent bibliometric analyses we decided to select a sample of the total “most relevant articles” for each dataset (WoS ranking criterion based on the degree of overlap between search terms and bibliographic fields in the record). The criterion of the most relevant articles is appropriate for our study because our aim is to compare ecological research between the tropics and temperate regions in relation to the ecological publications that are most visible within the global universe of data (note that the temperate and tropical regions are subsets of the global dataset). Furthermore, the choice to include a sample from the “global” dataset is justified by the fact that the response in our work may depend not only on the number of articles from each region, but on the extent to which articles from each region are absorbed into our knowledge. Therefore, comparison with the sample of the most relevant articles from the global universe of Ecology in WoS can be an excellent criterion, as it highlights the location of the most important tropical and temperate topics. In the case of the temperate and tropical datasets, we exported the total number of articles found within the WoS area “Ecology”. We then selected 14 pieces of information to be extracted from the articles: title, author keywords, year of publication, abstracts, citations, access number, references cited, author affiliation, source, addresses, funders, type of document. The selected metadata was exported in bibTex format for further processing and analysis.

In order to facilitate database standardisation, we limited the main analysis to WoS core collection, which brings some linguistic limitations, and leads us to assume the existence of a bias in the main analysis. However, in order to reduce this linguistic bias given the importance of science published in languages other than English, particularly in the biological sciences (Amano et al., 2021), we performed the same search for the ‘all collections’ option of WoS (Table S2), which includes: The Chinese Science Citation Database, the Korean Journal Database supplied by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), the Russian Science Citation Index, and the Scientific Electronic Library On-line (SciELO) which is the main database of journals in Spanish and Portuguese. We export the available metadata of total resulting articles: titles, authors, country, languages, affiliations and sources in order to later complement the comparative analysis.

Social variables such as geopolitical class (North-South) and data on countries' Gross Domestic Product per capita (GDP) were extracted from the World Bank database (World Bank, 2023) for the corresponding periods (we used the average GDP per period per country). The criteria for country names and definitions were determined according to the UN list for each period. It is also noteworthy that, with the exception of Australia, all Global North countries are in the temperate region, while 85% of Global South countries are in the tropical region.

Data analysisThe data analyses were, firstly, data collection followed by descriptive analysis for each level of analysis (each dataset). Secondly, the bibliometric techniques were developed (again for each dataset independently). The bibliometric analysis was carried out using the bibliometrix R-Tool (Aria and Cuccurullo, 2017), which is the most complete bibliometric analysis package, as it employs specific tools for both bibliometric research and quantitative scientometric research and data visualisation (Aria and Cuccurullo, 2017). This package is also the one that has shown the best performance in scientometric analysis (Moral-Muñoz et al., 2019). We used bibliometrix to evaluate the social structure, which aims to demonstrate the interaction of authors, institutions and countries through the analysis of collaboration networks. We carried out analyses of variance (ANOVA) and correlation, after testing the assumptions of normality and homoscedasticity, using the vegan package in the R software (R Core Team, 2020).

In terms of conceptual structure, we configured bibliometrix to identify the 100 most frequent concepts present in each dataset (Global 1960–1999, Global 2000–2020, Temperate 1960–1999, Temperate 2000–2020, Tropical 1960–1999, Tropical 2000–2020). We chose to use author keywords as they are the best way to evaluate articles, as they offer direct information on the central topics and methods of approach put forward by the authors, making the assessment of the relevance and reliability of the content more robust. In addition, the frequency of concepts reflects the ability of knowledge to circulate in the scientific community. We exported the list of words from each dataset and cleaned it by removing uninformative concepts (e.g. “suggested”, “different”). When a synonym was identified (for example, “tropical” and “tropic”), we added up the total frequencies of the terms and added the next most frequent concept to the list of most frequent words identified by the program. We created a relative frequency matrix with the most frequent topics. We calculated the relative frequency of the topics for each dataset by dividing the frequency found for each topic by the total number of topics for the corresponding dataset. In addition, as our aim is to understand the relationship between the six datasets, we analysed the unique and shared concepts between the datasets by period, by visualising them in a Venn diagram.

We performed the same process (description of social factors and subsequent text analysis) for articles in other languages, comparing the 100 most frequent words in the tropical and temperate dataset. We performed this analysis using the tidytext and stopwords packages in R software (R Core Team, 2020).

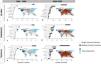

ResultsScientific production in ecology has been distributed heterogeneously around the globe, with most of the knowledge being generated in the Global North (Fig. S1). The number of articles published in Ecology has grown strongly over the last six decades, as have the number of authors per article (Table 1). We also found that articles mentioning “tropic” were approximately twice as numerous as those mentioning “temperate” in both periods. The gross domestic product (GDP) per capita of the countries positively affected the number of articles published by the countries in all six data sets (Fig. 1). In the global dataset, however, the relationship became less strong in the period from 2000 to 2020.

Key informations extracted from the datasets.

| GXX | GXXI | TRXX | TRXXI | TEXX | TEXXI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Doc WoS | 136061 | 319057 | 3790 | 18311 | 1577 | 9609 |

| Doc analysed Bibliometrix | 10000 | 20000 | 3790 | 18311 | 1577 | 9609 |

| Authors | 13127 | 52543 | 5681 | 44856 | 2947 | 27597 |

| Single-authored docs | 3302 | 891 | 1192 | 1071 | 435 | 456 |

| Co-Authors per Doc | 2.3 | 5,24 | 2,31 | 4,48 | 2,38 | 4,4 |

| International co-authorships % | 11.62 | 45,37 | 16.86 | 50,64 | 13,79 | 35,48 |

| References | 235152 | 530676 | 84360 | 453073 | 50286 | 312677 |

| Author's Keywords | 12750 | 41569 | 7247 | 36333 | 4452 | 24624 |

GXX: Global 1960–1999; GXXI: Global 2000–2020; TRXX: Tropical 1960–1999; TRXXI Tropical 2000–2020; TEXX Temperate 1960–1999; TEXXI Temperate 2000–2020.

Effect of geopolitical status (Global North or South) and Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per country on the total production of articles for each database. (a) n = 136061, (b) n = 319057, (c) n = 1577, (d) n = 9609, (e) n = 3790, (f) n = 18311. The total number of articles for each region was extracted from the main Web of Science collection according to the searches detailed in Table 1. The group of countries in the Global North are identified in red and the countries in the Global South in blue.

The countries that contributed most to global scientific production in the field of Ecology during the 20th century were the United States (USA), followed by the United Kingdom (UK), Canada and Australia (Fig. 2a), and they remained at the top of the ranking in the 21st century. Accompanying its strong scientific and technological development, China, which occupied 29th place in the 20th century, moved up to second place in the 21st century. In the temperate data-set, the main players are the same as mentioned above, but with important contributions from Japan, Spain and Chile (Fig. 2c and d). In the tropical data-set an important highlight is Brazil, whose scientific production in Ecology rose to second place in the 21st century, only behind the USA (Fig. 2e and f). Other key countries that deserves to be highlighted in tropical research are Mexico and India. Notice also considerable advances in several African and South American countries.

Distribution chart of the ten countries with the highest number of correspondence authors by region and period in descending order. The bars show the number of articles by authors from a single country (light gray) or authors from multiple countries (dark gray). For each region/period, the map of international collaboration is also shown. The darker the country on the map, the greater the number of collaborations from that country. In gray, countries with collaboration n = 0. The red lines connect the collaborating countries.

International collaboration in the scientific production of ecology intensified during the period 2000–2020, which can be seen by the increase in the frequency of articles with authors from more than one country in all databases (Fig. 2). The intensity and structure of the network of international collaborations in the field of Ecology has changed considerably over time (Fig. 2). Between 1960 and 1999, the United States was the central node of the collaborative networks between countries in the tropical and global dataset, so we can say that it was the structuring country of the international cooperation network, while the network for temperate ecology was more fragmented (Fig. S2). In 2000–2020, the European Union and the United States formed two large modules, sharing the international cooperation space in the three data-sets (Fig. S2). However, Brazil, Mexico, Costa Rica and Panama formed an independent module in tropical ecology (Fig. S2).

The geographical distribution of citations indicated that the countries that received the most citations in the temperate region in the period 1960–1999 were USA, UK and Australia (Table S3). Although the contribution of southern countries in the temperate region is greater, citations do not follow this pattern. For example, Argentina and Chile, which have a significant output of articles in the temperate region, are cited less than other countries with less output of articles. In the tropical region we see the same pattern. USA, UK and Australia are the most cited. Brazil and Mexico are cited less compared to their position in the production ranking. Once again, China has a prominent position in the ranking. No other country from the tropical regions or the Global South appears in the ranking of the first 10 countries.

The conceptual networks highlight the drastic change that has taken place in ecology, from a more “pure” science in the 1960–1999 period, focused on understanding natural processes and patterns (e.g., competition, predation, disturbance, seed dispersal, species richness), to an applied ecology in the 2000–2020 period, related to anthropogenic impacts (climate change, biodiversity, conservation, monitoring) (Fig. 3). The conceptual pool of ecology papers showed that many key ecology concepts are shared between the three databases in both periods (Fig. S3 and Fig. S4). In the period 1960–2000, however, some keywords in the global database were more prominent than in the tropical and temperate databases, such as those related to evolutionary ecology, sexual selection, molecular methods and metapopulations. In the second period, there was a decrease in these keywords associated with evolutionary ecology, and keywords associated with applied ecology and soil ecology appeared more frequently.

Relation of the main topics in each region and for each period. Each network is calculated from the 50 most frequent topics, associated by the Louvain algorithm. Groups of circles of the same colour indicate a module. The size of the circles is proportional to their frequency of occurrence in the literature analysed and the thickness of the links between nodes (topics) is proportional to the co-occurrence between two topics.

The number of top-hundred title words shared by the three datasets increased between 2000 and 2020, while the number of words unique to the temperate bank decreased sharply, and that of the tropical region remained similar (Fig. S3 and Fig. S4). We also observed that global datasets are more similar with temperate ones in both periods analysed. It is important to note that for both periods, the temperate and global regions are more similar to each other than to the tropics (Fig. S3 and Fig. S4). In the temperate region we see the formation of modules with central concepts associated with the ecosystem approach, aquatic ecology and climate change, while the tropical region is structured in modules associated with habitat loss and fragmentation and biodiversity conservation. The temperate ecology of the core collection WoS is more similar to the most relevant of the global ecology and the tropical ecology has its own characteristics.

We found 3886 articles published in languages other than English (1128 temperate and 2758 tropical). For the social structure (the pattern of authors’ institutional and national affiliations) we observe a similar pattern, while in the first period the authors are mainly from countries of the Global North (especially France) in the second period China, Mexico, Brazil and Chile are the countries with more production (Fig. 4). The same happens with the languages, we observe that the main language of publication of the articles changes from French to Spanish and Chinese in the second period, both in articles from the tropical and temperate regions (Fig. 4). In relation to the topics, the pattern of many localities among the main topics was also maintained, but this in both the tropical and temperate datasets. We also observed a large number of specific taxa as important words (Fig. 4). In relation to the approaches, we found less emphasis on topics related to ecosystem ecology, and more topics associated with population and community ecology, but this for both datasets, i.e., we found no major differences between the temperate and tropical datasets.

Total number of articles produced in languages other than English, considering authors from 15 countries (bar chart). In red, countries from the Global North; in blue, countries from the Global South. Pie chart showing the proportion of languages for each dataset by period (Tropical and Temperate).

Ecology is becoming a very strong collaborative science worldwide. Tropical and temperate research, however, exhibit great asymmetries in their geographical and social structural dimensions. Analyses of collaboration, citation and authorship show an extremely unequal scenario between and within the global, tropical and temperate databases. Our findings point to a general under-representation of scientists from the Global South as lead authors of studies carried out in the tropics/Global South. This low representation of local authors is in line with trends observed in other work. Four decades ago, a study that analysed articles published in the journals Biotropica and Ecology concluded that 66% of “global” tropical studies were conducted in just eight Central and South American countries, with Costa Rica and Panama leading the way, while studies conducted in Africa accounted for just 5.7% of publications (Clark, 1985). Also, it has been demonstrated that more than half of the publications in ecology are based on research carried out in just ten countries, and the majority of studies had lead authors from a North-Global country (Stocks et al., 2008; Cayuela et al., 2018).

The legacy of colonial history and imperialism can be clearly distinguished in the pattern of international collaboration. For example, European countries tend to collaborate more with their former colonies in Africa, Asia and parts of South America. The same was found in another study where, as in our results, it was observed that Spain and Portugal do not follow the same pattern as the Nordic countries (Cayuela et al., 2019). On the other hand the United States collaborates strongly with Central and South American countries, where it still exercises some economic power. It is interesting to notice, however, that collaborative networks with countries from the global South is not new, it simply intensified and gained scientific visibility. As supported by the global history of biological science (Barahona, 2021), if we examine history through the circulation of knowledge, people, and artifacts, it becomes apparent that contemporary ecology would be substantially different without the contributions of researchers from the Global South and the ecological knowledge of local and indigenous communities. Their work has shaped field practices, long-term observations, and site-specific ecological understandings, influencing how research sites are selected, studied, and interpreted.

The geographical distribution pattern of collaborations and authorship also reveals some consequences of global geopolitical relations in science, such as the emergence of the BRICS (i.e., a bloc made up of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) and the European Union, as well as the effects of globalization and advances in the telecommunications industry associated with the digital economy, which have influenced the possibilities for collaboration. The changes in the pattern of collaboration within Europe between the first and second periods is noteworthy. In the twentieth century, most articles had authors from a single country, probably reflecting more local studies but also the geopolitical scenario and the intra-continental conflicts caused by the First and Second World War. Already in the 21st century we are witnessing an increase in collaboration between European countries, possibly reflecting the effects of the creation of the European Union, which since its establishment in the 1990s has allowed the exchange of students, researchers and ideas among countries, as well as the development of large-scale spatial projects and syntheses (Makkonen and Mitze, 2016). Similarly, the basis of the BRICS project is the idea of the emerging Global South, with horizontally structured collaboration, including the strengthening of South-South relations at the academic level through strong funding of local public institutions (Khomyakov et al., 2020; Amirjalili et al., 2024). As we observed in our results, this is especially evident in China, which has a long institutional investment project for the development of science and technology (Law, 2014). And also, in Brazil, where the investments in education and solid scientific development in the first decade of the 21st century has strengthened science not only in the country, but also in the region (Leite et al., 2011). We highlight the potential for a more ample collaboration among South American and African countries in the next decades.

The increase in the number of authors from the South countries should be viewed with caution, for at least three reasons. First, because we show that the most cited authors continue to be from the North. This is consistent with other studies, in which authors analyzed papers published between 1975 and 2015 by ecologists working in Argentine, Brazilian, Chilean, and Mexican institutions and observed that, while the number of publications grew exponentially, the number of citations per article declined (Rau et al., 2017). That is, it is not that there is no science being done by scientists in the South, but rather that the most cited science is that of the North.

Secondly, because we cannot definitively assess who drives research agendas and who actually contributes content, knowledge, and material support through this type of bibliometric studies. For example, an analysis of the specific trajectory of collaborations in the tropics shows that, although the proportion of authors based in tropical countries has increased, co-authorship links between tropical and extratropical countries did not increase over time and that their emergence was mainly associated with the overall growth of multi-authored articles, rather than with a structural change in collaboration patterns (Perez and Hogan, 2018). In other words, as in our work, the existing evidence on changes in collaboration patterns in the tropics does not necessarily reflect greater integration between the North and the South. What we observe is the growth of certain types of collaboration (often those that add co-authors), suggesting that some interregional collaborations continue to position tropical and/or Southern partners primarily as data providers, while analytical synthesis, model development, and conceptual leadership continue to be led by Northern institutions. Therefore, and thirdly, we must moderate general claims about “increased collaboration” and emphasize the need for complementary qualitative and demographic studies to assess who sets research agendas, interprets authorship, and controls data and resources.

Conceptual structureThe presence and absence of concepts in the analyses carried out reflect changes and advances, whether they are continuities or ruptures in epistemic evolution. The analysis of the relationships and frequencies of the concepts, the meanings of the groupings and hierarchies we find is conditioned by the contextualised understanding we have of our scientific field. Therefore, the analysis of the conceptual structure can lead to different paths, especially in view of the large volume of information that each concept and the relationships between them can mean. Here we highlight three: a common pool of concepts, a difference in epistemic approach between the regions and the geographic localization practice in ecological research practice. Finally, we discuss if Temperate ecology is a model of ecology.

A common pool of conceptsA considerable body of common concepts has been identified among the data-sets, representing the structural core of Ecology. In general, community ecology concepts prevail in both periods, as has been previously noticed (McCallen et al., 2019). Other general trends can be seen, such as the increased frequency and centrality of the topic “climate change”, the emergence of macro-scale topics and the increase in topics related to new methods and statistics, which is to be expected given the advancement of computer and geospatial technologies and the accumulation of large-scale ecological datasets (Lander, 2005). We also observed, as in other works, a shift from studies on single biological systems, to research carried out at ecosystem and community level (Knott et al., 2019; McCallen et al., 2019; Anderson et al., 2021; Zettlemoyer et al., 2023).

Different research approachesThe most frequent keywords and co-occurrence networks show a clear difference in approach between tropical and temperate regions. While in the tropical region topics such as biodiversity, conservation and aspects of community structure are more frequent and central, in the temperate region concepts associated with ecosystem ecology, aquatic ecology, experimental ecology and climate change dominate.

The ecosystem approach is seen as emblematic in understanding the historical development of ecology (Kormondy, 2012). In a survey conducted among members of the British Ecological Society, ecosystem was identified as the most important concept in ecology (Reiners et al., 2017), and second in a similar survey at the Ecological Society of America (Carmel et al., 2013). Therefore, the centrality of topics associated with ecosystems in temperate datasets has a historical explanation linked to the development of global ecology per se. On the other hand, the strong development of ecosystem ecology is associated with a strong investment in large empirical and experimental research programs, such as the International Biological Program (IBP), which focused on consolidating ecosystem ecology (Yu et al., 2021), or the Long Term Ecological Research (LTER) Network (Knapp et al., 2012). This also explains our results, given that researchers have found that there is a geographical bias in the distribution of these types of programs, since experiments in tropical regions represent only 13% of the total (Clarke et al., 2017). In addition, specific regions dominate the experimental sites, for example, in the tropics 42% were carried out in Costa Rica and within the temperate zone, the majority of studies were carried out in the USA and northwestern Europe (Clarke et al., 2017).

Although our data do not allow us to directly assess intentional constraints, the formation of thematic groups in Ecology may be associated with structural inequalities that have limited the development of experiments and research requiring greater resources and funding, as well as forms of institutional or infrastructural control that concentrate access to data sets or certain research locations in institutions in the Global North. These processes, whether intentional or resulting from the very organization of the scientific system, can influence who is able to produce knowledge about certain ecosystems and thus shape which perspectives become most central to global ecological narratives. This may have contributed to the greater development of ecosystem research in temperate regions (although it is worth examining more closely the case of temperate regions in the Global South with strong research activity, such as Chile and Argentina), while in tropical contexts, we observe a predominance of approaches focused on applied ecology. However, this pattern may also reflect how researchers working in tropical contexts have shaped research agendas based on locally relevant problems, as well as the role of specific researchers linked to biological research stations and sites, as in the case of Central America and the development of research in Barro Colorado, Costa Rica. In this sense, the prominence of applied ecology in tropical research not only signals a constraint, but also points to context-dependent forms of knowledge production that have contributed to reorienting ecological concerns on a global scale.

The distribution of certain terms across regions also reveals how the construction of ecological knowledge can dilute or neutralize sociohistorical processes. For example, the fact that “deforestation” appears predominantly in the tropics, while terms such as “colonization” or “extractivism” are absent, reflects broader trends in scientific language to depoliticize environmental transformations and separate them from the historical and material relations that shape them.

Finally, the differences found and emphasized do not imply that there is no research of one type or another in both regions, but they highlight the pattern of topic selection associated with scientific production that mobilizes the categories “tropical” and “temperate.” A relevant implication of this finding is the need to examine, in future research and debates, the processes by which global scientific agendas are structured: which topics are prioritized or marginalized and how the allocation of resources and the establishment of collaborations can be optimized to address ecological challenges shared by both regions.

The localization practice in ecological research practiceThe higher frequency of specific terms denoting the geographic location of the studies as key concepts in the tropics highlights an important difference in the criteria for selecting concepts. The decision to include the country of the research location, or the specific tropical system (e.g. Tropical rainforest) can result from a variety of motivations, both on the part of editors, reviewers and authors. For example, some may think that tropical or southern studies are more interesting to highlight in titles to attract readers, or because they will draw attention to the novelty of the research, given the knowledge gaps that often exist in these areas. But despite these reasons, there is evidence that this practice represents a systemic problem within the academic system.

In several subfields of social sciences, the same pattern was observed in titles of more than half a million articles (Torres and Alburez-Gutiérrez, 2022). The degree to which the regional focus of a study is explicitly declared upfront was named “localization practices”. They argued that publications follow a power-based logic between centres of academic production and the periphery. Researchers studying the Global South are more likely to declare their geographical focus, signalling – consciously or unconsciously – the specificity and non-universality of their work, and the opposite for research from the North, where no concrete geographical reference is included in their titles (Torres and Alburez-Gutiérrez, 2022). Studies in Social Psychology show the same phenomenon (Kahalon et al., 2022). The point is that readers normally interpret these “delocalized” titles as describing universal processes.

Our results tend to follow this pattern, where work produced in and about the global North is considered more “universal”, so that even when research is carried out in temperate regions, the term “temperate” is not used, which is confused with global. The evidence produced in the global South, on the other hand, is considered to be for specific (i.e. “localised”) contexts. It should be noted that even in the temperate region, with the exception of Australia and New Zealand, the country that appears among the most frequent words is Chile, a country in the Global South, even though in our search we filtered for articles that mentioned the term ‘temperate’. Likewise, in the results of the most frequent words in the titles of articles in other languages, we observe that both in the temperate and tropical regions, specific locales of the Global South appear. We understand that this result coincides with the practice of localisation in ecological research, and thus demonstrates that power and territory, formerly space and knowledge, are key elements in understanding the structure of ecology.

Temperate ecology as a model of ecologyThe understanding of the ‘global’ in ecology is influenced by a predominantly temperate perspective, thus supporting the temperate bias hypothesis. This occurs because the bulk of the ecological knowledge was produced in the temperate region, and/or because the research considered as most relevant and the most cited authors are from temperate areas, and/or because temperate research frequently do not use this term and understands itself as global (which is related to methodological globalism). But how can we tell whether temperate ecology is what structures global ecology or whether it is just a subset of “global” ecology? Sartori (1970), in a classic work in social sciences, defined that there are two types of universality when it comes to the use of concepts: empirical and that imposed by what he calls “conceptual extension”. Social studies of science have shown that conceptual extension takes place in a unidirectional way influenced by the coloniality of knowledge in science (Lander, 2005). Thus, we can interpret from our results that there are conceptual extension practices with a universalising nature in Ecology, i.e., an imposed universality. Firstly, because Ecology as an institutionalised scientific field arose in temperate areas, in the Global North, so it is to be expected that the direction of conceptual extension would be from North to South, as happens in other scientific fields (Gaspar, 2019). And, second, because our results of the social structure indicate that those who publish most and/or from where ecological knowledge is institutionally generated are in the richer countries with colonial histories over the territories of the South. This does not mean that no research is produced in the tropics, but that, according to our results, it has occupied a less central position in global ecological knowledge networks.

ConclusionsRobert Paine (2002) questioned the nature of paradigms in ecology, whether they represent legitimate differences or are the result of restrictions or advantages imposed by the research material. Paraphrasing Paine, we could ask: Do Tropical and Temperate Ecology have legitimate differences (in an epistemological way) or are the observed differences the result of historical restrictions or advantages? Our work shows that there are both differences and similarities, and that the differences in approaches tend to be explained by historical “advantages” and “constraints”, i.e., that biases are constructed by historical factors.

We conclude that the North-South inequality is transferred to the Temperate-Tropical relationship, and that this is not just a geographical coincidence, but a historical consequence of power relations. However, it is important to emphasise that “North” or “South” is not an intrinsic characteristic of certain fields, networks or institutions, but a relational position in an international scenario of knowledge production. That is, that both are internally hierarchical and similar asymmetries can be found within a country, a region and even an institution, due to social, racial and gender biases. This is why it is important to emphasise the dynamics of the circulation of knowledge, people and scientific practices. We showed that the scientific work of southern and tropical countries is a fundamental part of the structure of ecology, because by being part of international collaborative networks, the knowledge generated in the South circulates and forms part of the consolidation of ecology on a global scale. We hope this research will increase the awareness of the historical construction of the North American and Eurocentric paradigms in ecology. Furthermore, we argue that specific institutional and funding mechanisms should be developed to identify and address persistent knowledge gaps in tropical regions, strengthen South-South research networks through long-term collaborative programs, and promote more equitable practices of authorship, data sharing, and agenda setting in order to better integrate diverse forms of ecological knowledge at the global level.

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Thomas Lewinsohn, Dr. Luiz Roberto Ribeiro Faria, Dr. Rodrigo Carmo, and Dr. Cristina Baldauf, for their important contributions to the improvement of this final version of the manuscript. This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nivel Superior – Brazil (CAPES) – Finance Code 001. MNCH received a PhD studentship from CAPES. CRF was supported by CNPq (PQ 306812/2017-7).